David Miller has a reflection on the (incessant) push for academics to get onboard with the AI revolution:

Let me counter Caylor’s 1960’s math professor analogy with an example from sports. Attempting to outsource the “chores” of brainstorming and the hard work of crafting sentences to a large language model is like getting a robot to run your basketball drills so you can spend more time playing the game. With critical thinking as with any other skill, there is no substitute for practice. And the foundation of critical thinking is basic literacy. As David Brooks puts it:

“[L]iteracy is the backbone of reasoning ability, the source of the background knowledge you need to make good decisions in a complicated world. ... Writing is the discipline that teaches you to take a jumble of thoughts and cohere them into a compelling point of view.”

In other words, Caylor and other AI cheerleaders miss the whole point of education. Our responsibility as teachers includes helping students learn what it means to work with their minds, and prompting them to forge the neural pathways that will enable them to think creatively and make difficult decisions. These critical thinking skills depend on the “chores” of reading and writing, and they are even more essential in a world where truth and lies are so thoroughly mixed together.

****

The New York Times has a longform essay on ADHD:

It’s been an eye-opening experience for me these last four years as I have been teaching middle school and high school students. I have seen the the increase in ADHD diagnoses especially among the boys as more and more schoolwork moved online and kids, in general, spend an increasing amount of time in front of screens.

I wish there was a way to bring back apprenticeship opportunities for teenagers that would allow for more tactile learning opportunities. My dream: starting a classical Christian school with trades built into the curriculum. Something like this, but at the high school level.

****

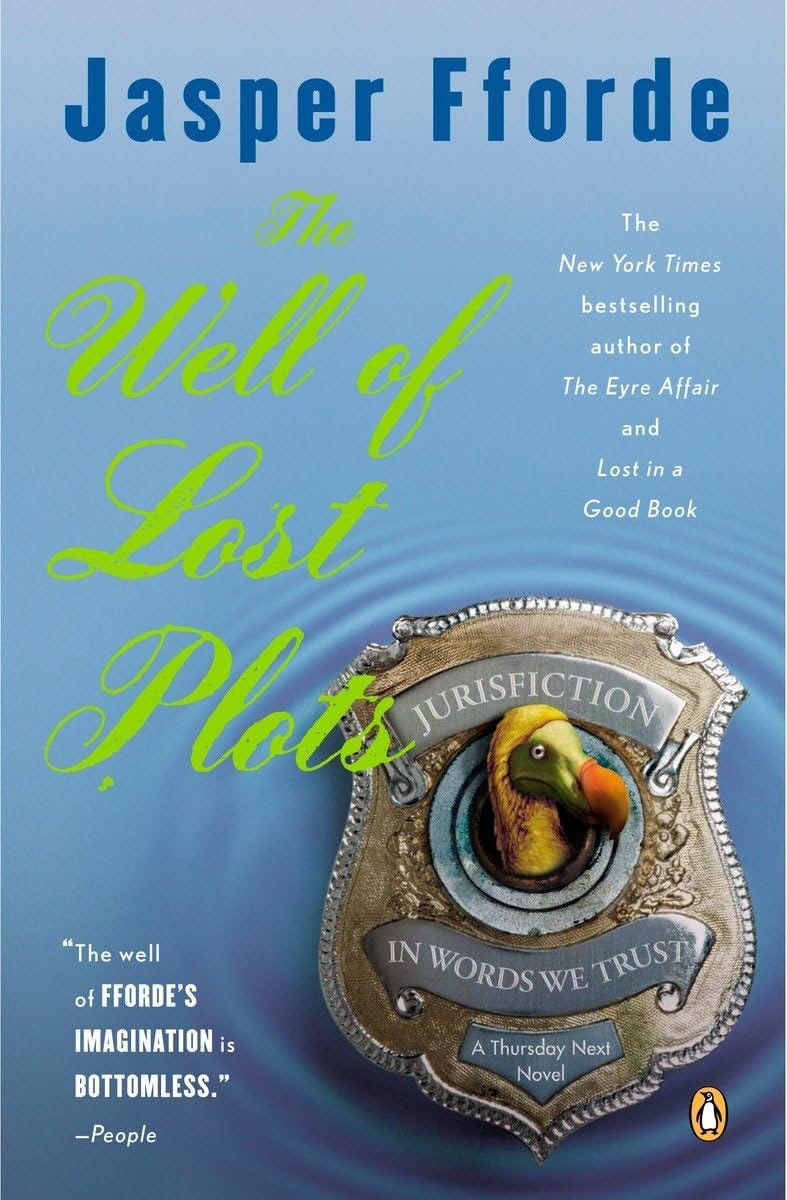

In print, I am working my way through the Thursday Next series by Jasper Fforde. This week, I started the third book, The Well of Lost Plots. It opens with an interesting observation: what would it look like to live in a book? What would be easier? What wouldn’t exist?

“All the boring day-to-day mundanities that we conduct in the real world get in the way of narrative flow and are thus generally avoided. The car didn’t need re-fueling, there were never any wrong numbers…There were other more subtle differences, too. For instance, no one ever needed to repeat themselves in case you didn’t hear, no one shared the same name, talked at the same time or had a word annoyingly ‘on the tip of their tongue.’

…But there were some downsides…There was a peculiar lack of cinemas, wallpaer, toilets, colors, books, animals, underwear, smells, haircuts, and strangely enough, minor illnesses. If someone was ill in a book, it was either terminal and dramatically unpleasant or a mild head cold — there wasn’t much in between.”

What are you reading?