Myles Werntz has the best theological take on the de-formational aspect of AI usage especially for college students. Examining the ethics of AI usage through the lens of virtue ethics and moral formation, Werntz argues that the use of LLMs and other AI tools work against the cultivation of virtue, especially against the cultivation of the four cardinal virtues: prudence, temperance, fortitude, and justice.

As he turns to the virtue of justice, he considers the current argument that allowing students to use AI is a justice-issue, and that not allowing students to use AI is a grave injustice. He writes:

Thus far, ChatGPT seems to have failed on three of the four basic virtues. But perhaps justice requires us to invite everyone to use such an equalizing tool?

Again, I think the answer must be no. There’s a rudimentary fairness to letting all students use LLMs—but also a deeper injustice. Training students to use and even rely on AI does not give them what they need to flourish intellectually or morally as God’s creatures. This is a severe injustice. As I put it to my students, the problem is less their violation of academic integrity than the fact that they robbed themselves of what was rightfully theirs in the educational process.

***

Porter Taylor has a beautiful reflection on the life and influence of Fleming Rutledge, one of my favourite preachers:

Through her books, sermons, and lectures, Fleming Rutledge has shaped a generation of preachers, theologians, and laypeople. She writes with theological depth and prophetic clarity, bridging the pulpit and the page with unmatched conviction. Her sermons are thunderclaps of grace—fierce, faithful, and always grounded in the cross of Christ.

She has given the church a language for hope in the face of despair and a grammar for grace in a world of judgment. Her influence echoes from Episcopal pulpits to evangelical classrooms, from mainline pews to Reformed seminaries. In a time of shallow spirituality, she has insisted on the God who acts, judges, delivers, and saves.

And perhaps most of all: she has never stopped taking the gospel seriously.

***

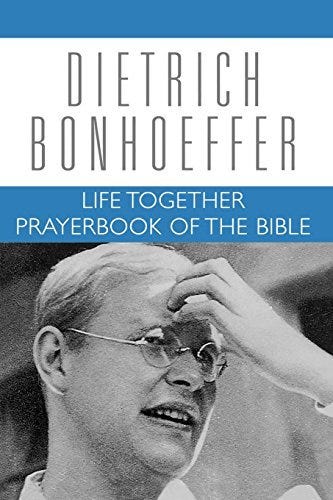

Another school year has started which means I’m reading, and re-reading, as I prepare for my classes. This fall, one of the classes that I’m teaching is an introduction to spiritual formation in which we’ll read Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s Life Together. Every time I re-read this book, I am enriched. Now that I’m back in Canada, after having spent four years in South Carolina, Bonhoeffer’s writing takes on a different tone as I try to re-orient myself to living in a post-Christian country. I’m particularly struck by Bonhoeffer’s description of how the gathering of Christians in community is a grace:

“Thus in the period between the death of Christ and the day of judgement, when Christians are allowed to live here in visible community with other Christians, we have merely a gracious anticipation of the end time. It is by God’s grace that a congregation is permitted to gather visibly around God’s word and sacrament in this world. Not all Christians partake of this grace. The imprisoned, the sick, the lonely who live in the diaspora, the proclaimers of the gospel in heathen lands stand alone. They know that visible community is grace. They pray with the psalmist, “I went with the throng, and led them in procession to the house of God, with glad shouts and songs of thanksgiving, a multitude keeping festival” (Psalm 42:5). But they remain alone in distant lands, a scattered seed according to God’s will. Yet what is denied them as a visible experience they grasp more ardently in faith.” (Bonhoeffer, Life Together, pg. 28).

What are you reading? Let me know in the comments.