The Women and Theology Research Database

An introduction to a research project I have had the privilege of curating.

In her essay on issues of historiography, Margaret Lamberts Bendroth writes: “few people would argue against including women in history, but not everyone can agree on where to include them or how their inclusion should change the story as a whole.”[2] This question is not limited to the field of history. The same question can be asked in relation to the field of theology. And this is a live question today. How might we include women’s writings in a discussion of theology?

There are several possibilities. First, we may include women’s theological writings because they speak to women’s issues. Thus, we might include a woman’s work because of her theological anthropology of womanhood, marriage, children, etc and her interpretation of texts like Titus 2, 1 Timothy 2:9–15 or Ephesians 5, or because she directly addresses the role of women in the church and in society. While important, this can pigeonhole women, and give the appearance that, as representatives of female theological scholarship, these women only spoke to a narrow topic. They are then excluded from the bigger themes and issues of their day by modern scholars who are tasked with teaching the history of theology with broad strokes.[3]

Second, we might include women’s work because their writings represent something unique or niche. In this case, we might include a female theologian because she presents an idea that is obscure, and modern scholars can use her to demonstrate a theological curiosity that is not meant to be taken seriously or incorporated into the mainstream presentation, but is included instead to create controversy or intrigue. We see this very often in theological surveys or volumes on the development of theology. There may be a chapter tacked on near the end on Feminist theology. This framing then gives the appearance that women have only be interested in theology since the 1970s and only do theology as a means to create controversy and upend the patriarchy.

Third, and closely related to the second option, we might include a woman’s theological treatise as an example of theology gone wrong. Thus, we might include the writing as a way to show the dangers of uneducated, or unauthorized ideas. This risks shutting the door on further inclusion of women’s theological treatises, because her ideas (and, through guilt by association, other female theologians) are too far outside the scope of mainstream or orthodox theology.

But what if there was a fourth option? What if we included women’s theological work precisely because of how mainstream and ordinary it is? What if we included the writings of women, not because of peculiarity or controversy, but because they represent key interpretive ideas?

But how do we take this fourth option seriously and put it into practice? One of the biggest hindrances is availability of resources. How many of us have been in a theology class or in a theological library engaging with sources and notice that they are all men? What do we conclude? The standard answer is: well women didn’t write theology back then.

This is just untrue. Women have been writing theology just as long as men. But there are some key differences:

Many of their writings have been forgotten.

Many of the treatises were not academic. Many were catechetical materials for teaching Sunday school or other women. Many were devotional materials, letters, and poems. This means that the work of recovering and incorporating the contributions of women to the field of theology requires cross-disciplinary skills and often times more work as we see to articulate and summarize their theological contributions.

It is this work of discovery and recovery that has captured my imagination and led to the creation of a very special project: The Women and Theology Research Database.

Background

I originally conceived of this project in 2016 after having taken a class with Marion Taylor at Wycliffe College. She is the co-editor of the book, Handbook of Women Biblical Interpreters. This reference work has short, medium, and long entries on a variety of women who have commented on and interpreted the Bible, across centuries, continents, and traditions. But the focus there is largely on biblical interpretation. While there are some explorations of theological themes, that is not the focus of the volume. And so Marion suggested a companion volume. What would it look like to have a resource on women and theology?

As I began to catch a hold of the possibilities, I realized a couple of things.

1. I wanted all of the sources that I was finding to not just be mine. What would it look like to have an online research database?

2. While a resource like Handbook of Women Biblical Interpreters is important, it is also important to have a theological volume that could be easily accessed and updated regularly.

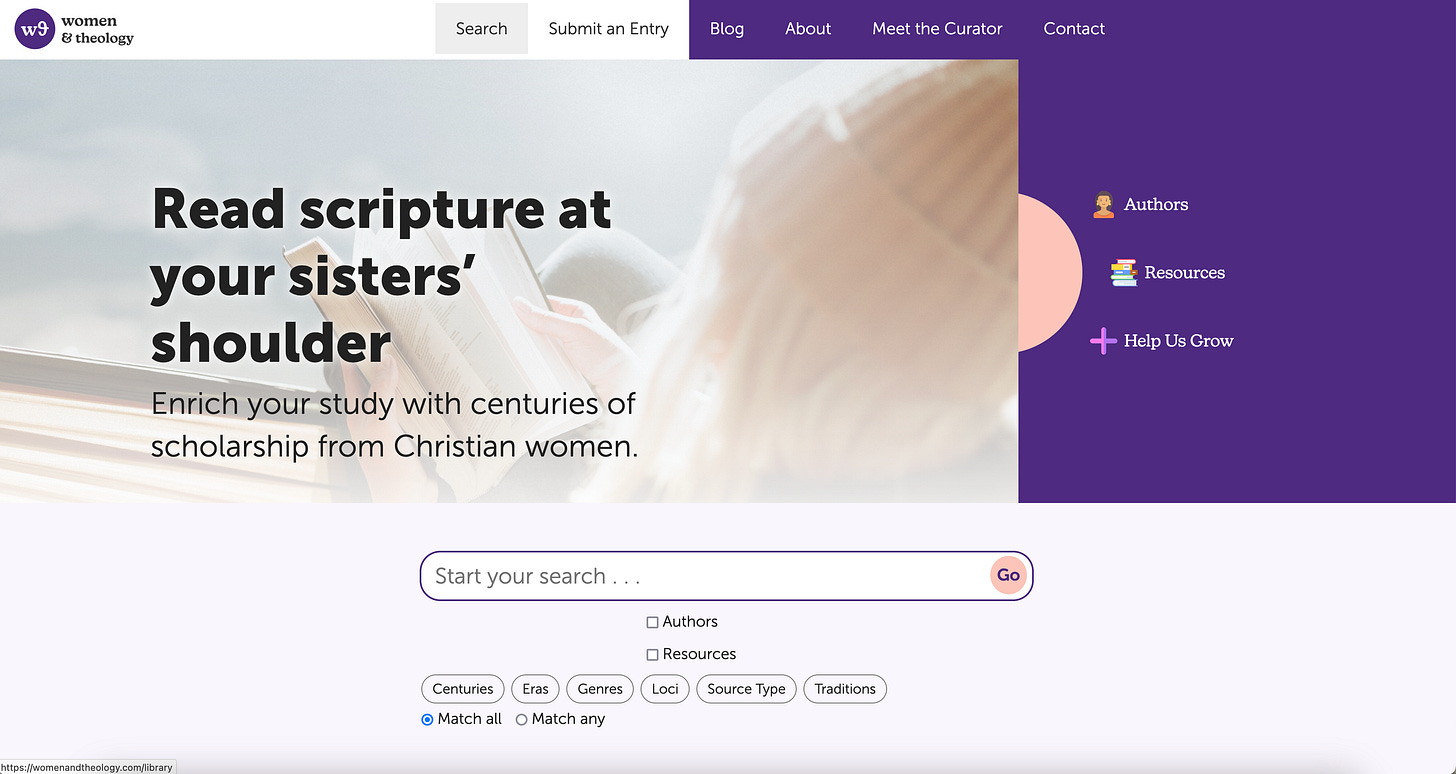

And so I set to work. Building a database was the first step. With the help of web-developer Luke Johnson, I have created the Women and Theology Research Database. As of this writing, there are 424 women and nearly 1,394 primary and secondary sources. You can search by era, tradition, and theological topic.

The second step was to start a conversation. Hence the Theology with Dr. AM Hackney podcast. Between the podcast and the research database, I hope to spark conversations about theology and about ways to include and incorporate women in theological discussions. The podcast is a series of theological discussions of ordinary topics within the field of systematic theology, that just happen to be done by a woman, me. For this, I will draw on my own theological research and from my years of teaching theology at the college and seminary level.

The third step is The Catechist’s Quill. I want to write in the middle space between books and life. One the one hand, I want to write robust theological volumes that are accessible to an educated lay person in the church. Thus, my two current writing projects are a book on how to read Scripture theologically and a systematic theology for kids (aimed at 9-12 year olds). On the other hand, I want to write in such a way that gives space for theological reflection in day-to-day kinds of conversation.

So who am I?

My name is Dr. Amanda MacInnis-Hackney. I have a PhD from Wycliffe College at the University of Toronto. I have taught college and seminary classes in systematic theology, spiritual formation, and ethics for the last seven years. My main research area focuses on how theologians have read and interpreted scripture in their systematic theologies. My dissertation examined on Karl Barth’s exegesis of John 1 and its place in his larger Church Dogmatics. I am a conservative, evangelical, liturgical, high-church, charismatic Anglican. When I’m not talking about, reading about, thinking about, writing about theology, you will find me geeking out on all things sci-fi.

A word about current discussions about women and theology

If you spend any time on social media, you know that there is a raging debate between complementarian and egalitarian understandings of women in ministry. The downside to this debate is that it makes it seem like the only area in which women do theology is in relation to whether women can teach, preach, or be pastors. A similar thing happens with discussions of the apostle Paul and his letters. When I was in seminary, I kept putting off taking the required course on Pauline Epistles because the way the course was structured the professor spent 2/3 of the week-long intensive just on the issue of women and preaching. Finally, I couldn’t put it off any longer and I had to take the course. But that year, a different professor was taking it. That version of the course only had one afternoon devoted to the question of Paul’s view of women in ministry. As the professor explained, “Paul had so much to say about theology, Christian life, etc. The question of women in ministry is not nearly as outsized as we have made it.”

That is also true about women and theology today. Not all women who do theology are focused in on questions of gender, women’s roles, and marriage. When I was in seminary, there was a theology professor who insisted on calling me “the feminist theologian.” At first I thought it was just a joke, but I eventually realized that he was serious. One day, as we were passing in the hall, he greeted me in his typical manner, and I turned, very politely, with a laugh in my voice, and replied, “Actually, I’m not a feminist theologian, I’m a theologian who just happens to be a woman!” After I graduated, the professor asked if I would be willing to cover a lecture in his “Theology of Scripture” class while he was away at conference. I agreed, and asked where in the course material they would be that day. He explained that they would be on Karl Barth, but since I was coming, could I skip ahead and present on feminist interpretations of Scripture? I stood there in stunned silence. Was he kidding? Here I was, newly graduated, having spent a significant portion of my education, and including my thesis, on Karl Barth’s theological exegesis, and he wanted me to teach on an area I had no familiarity with simply because I was a woman. Probably with less tact that I should have mustered, I pushed back and said that I had no training or experience with the feminist literature, but I would be happy to lecture on Karl Barth.

I tell this story because it is emblematic of how I understand my faith and my work as a scholar. I am a theologian who just happens to be a woman. I’m not interested in feminist hermeneutics. My passion is systematic theology and while I have written and published for academia, my heart is to make theology accessible for the church. I am a catechist. I love to teach people about theology, whether it is undergrads in a college classroom, an adult Sunday school class at church, or one on one mentoring conversations at the coffee shop. And this is because theology isn’t an ivory tower endeavour only for egg-head academics. As Beth Felker Jones defines it, “Theology is the discipline of learning from the Word of God and learning to use words faithfuly when we speak about God.”

And this definition is at the heart of my vision for the women and theology research database. I’m interested in highlighting women who have embraced their vocational calling to speak about God. In fact, this vocational calling is the calling of all Christians. If we speak about God, we are theologians. And so, while you may find resources in the database on the question of women in ministry, you’ll find more resources on Christology, Pneumatology, providence, eschatology, and all the other theological disciplines. So, I encourage you to check out the women and theology research database. And I hope that you will subscribe to the podcast and to this substack.

[2] Margaret Lamberts Bendroth, “Men, Women, and God: Some Historiographical Issues,” in History and the Christian Historian, ed. Ronald A. Wells (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1998), 91.

[3] An example of this is Stephen Westerholm and Martin Westerholm, Reading Sacred Scripture: Voices from the History of Biblical Interpretation (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2016). There is not a single female represented in the “history” of voices.